For the first two and a half years of Waylon Dutton’s life, he was a wild and curious boy who loved to play with trucks and tractors as his parents, Mystery Hill and Will Dutton, tracked his progress.

Then, the phone call came: “Something’s wrong with Waylon.”

While staying with Mystery’s parents, Waylon had made odd noises, stared off into space and briefly stopped breathing. By the time Mystery and emergency medical services arrived, Waylon was tired but conscious. That was weird, the family thought.

Two nights later, Waylon convulsed at the dinner table. This time, the family recognized it was a seizure and brought Waylon to the emergency room at Novant Health Ballantyne Medical Center where they learned that both episodes had likely been seizures, and that having two or more seizures more than a day apart often leads to an epilepsy diagnosis.

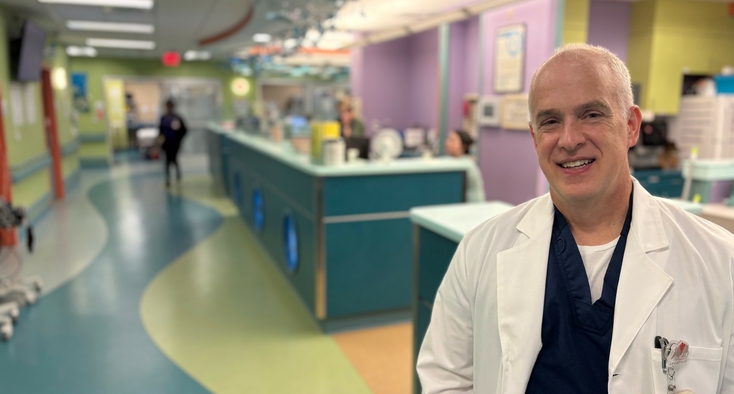

Soon they saw pediatric neurologist and epileptologist Dr. M. Ehsaan Shahnawaz of Novant Health Pediatric Neurology & Sleep - Randolph in Charlotte. (An epileptologist is a neurologist who specializes in epilepsy.)

After evaluation and neuroimaging, Shahwanaz (whose patients call him “Dr. Shah”) diagnosed Waylon with epilepsy — a brain condition that causes repeated seizures — and started him on an anti-seizure medication. The family hoped they had seen their last seizure.

They hadn’t.

Complete neurological care for your child.

Sleepless nights and worry-filled days

Roughly half of people with epilepsy will become seizure-free on the first seizure medication that they try. Waylon was not among them.

At first, most of his seizures happened at night. Mystery and Will moved Waylon into their bedroom, where they’d wake up to Waylon thrashing or moaning — if the parents had been able to fall asleep to begin with.

Like many parents whose children have epilepsy, they were worried about Waylon dying from a seizure, an event called SUDEP that caused the death of Disney Channel star Cameron Boyce in 2019.

Waylon could get injured during seizures, so the couple had to be vigilant and ready to perform seizure first aid. If a seizure lasted more than five minutes, they would need to administer rescue medication to prevent a long seizure that could lead to brain injury.

Even the smallest movements and sounds — normal for sleeping toddlers — set off mental alarm bells for his parents.

“You think in the back of your head while you're laying there, ‘Is that another seizure? Is this going to be the moment?’” Will said. “Some nights we sat up and just watched to make sure that he was going to be OK.”

Then Waylon began experiencing daytime seizures, too — and different types of seizures.

These included tonic-clonic seizures where his muscles contracted violently and he lost consciousness, gelastic seizures where he’d turn his head to the side and laugh stiffly, atonic seizures when he’d drop to the ground without warning, and back-to-back seizures called cluster seizures.

The family frequently saw Shahnawaz, who prescribed two more types of medications. The seizures continued.

Waylon was getting all the right care: He was seeing an expert and trying appropriate doses of well-chosen medications.

But he was in the 30% to 40% of patients with epilepsy who have drug-resistant epilepsy (also called “intractable” epilepsy). This condition is diagnosed only after a patient has tried two or more appropriate anti-seizure medications and is still having seizures.

‘You have options’

At the worst point, Waylon was having 20 seizures a day.

He wore a helmet to protect him from head injury. Scared family members weren’t comfortable watching him. Mystery quit her job so she could protect Waylon from injury and try to track seizure triggers.

A seizure could happen at any time, so they didn’t feel safe taking him out of the house. Not that Waylon was interested — he had stopped playing with toys and sat on the couch most of the day. He no longer tried to talk, communicating instead with hand flapping and sounds. He couldn’t walk consistently. During some of his seizures, he quit breathing and turned blue.

“I felt really lost and very helpless,” Mystery said. “We didn't know what the future was going to be like for him at that point.”

Shahnawaz referred Waylon to occupational and physical therapy and encouraged the family: You have options.

They felt fear. But their doctor saw bravery.

Epilepsy surgery wasn’t appropriate for Waylon’s case, so Shahnawaz presented two choices. The first was a restrictive ketogenic diet, which can be a good option for some but “can feel more invasive on a day-to-day basis,” Shahnawaz said.

The second was vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): an implantable device — kind of like a pacemaker for the brain — that delivers pulses of electrical energy to the brain through the vagus nerve, improving seizure control in many people with drug-resistant epilepsy.

Implanting the device requires outpatient surgery, which terrified the couple, but they understood how dire Waylon’s situation was. There’s a substantially higher risk of SUDEP when epilepsy is uncontrolled, and repeated seizures can impact learning and development.

Facing these realities is sobering, but “It’s surprising to me how much bravery families come in with,” Shahwanaz said. To help them make an educated decision, Shahwanaz connected the family with the VNS device manufacturer and pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. Erin Kiehna of Novant Health Pediatric Neurosurgery - Eastover, who was frank about the pros and cons.

In the end, the family decided to try VNS. “We knew it was kind of our last option with Waylon,” Will said. “These are the cards we're dealt, and we have to play them.”

From 20 seizures a day to zero

Waylon had the VNS device implanted on Nov. 1, 2024. For the next few months, Shahwanaz met regularly with the family, making adjustments to the device settings and medications as needed.

And in January 2025, they celebrated: Waylon was officially seizure-free.

Today, Waylon is 4 years old. He’s gone from three epilepsy medications to two, with hope of dropping to one someday. He’s also made developmental progress: he’s walking consistently and can say over 50 words. He’s playing with toys again, answering questions, and has started to approach other children to play.

Shahwanaz has seen Waylon monthly since he was diagnosed. He’s said that recently, he’s felt like he’s seeing "a whole different child.” His parents agree.

“All these developmental milestones he should have met by the time he was two, now it’s all taking place,” Will said. “He climbs up the steps by himself to go down the slide — he’s 4 years old, and we’re ecstatic.”

The couple has been able to relax for the first time in years, and they’re enjoying watching Waylon have normal childhood experiences like visiting the park. “It’s priceless because we didn’t know if he was ever going to be able to do any of these things,” Mystery said. “Now he has the chance for a normal life.”

Waylon is still in occupational and physical therapy, and he will start speech therapy soon. The couple is ready to celebrate as he reaches each milestone — at his own pace.

He’ll likely always require monitoring for his epilepsy, including ongoing adjustments to his VNS device, but things are going so well for now that he isn’t scheduled to see Shahnawaz for six months. “We’ve got him in a great place,” Shahnawaz said, adding that every member of the pediatric neurology/sleep team is responsible for the success — including clinical staff, clerical staff and the clinic’s referral coordinator.

Patients like Waylon are why Shahnawaz was drawn to pediatric neurology in the first place: “If I can help a child, I've changed their whole life course.”

Expert epilepsy care at Novant Health

Some 3.4 million people in the U.S. have epilepsy, including over 450,000 children like Waylon Dutton (see article above). More than 30% of people with epilepsy still experience uncontrolled seizures.

If you’re among them, or if you struggle with side effects from anti-seizure medication, have additional developmental or neurological concerns, want to explore additional treatment options, or simply want specialized care, it’s time to visit a comprehensive epilepsy center accredited by the National Association of Epilepsy Centers (NAEC). NAEC accreditation shows that the center has met the highest standards of care for epilepsy, with expert providers and comprehensive care.

Novant Health has three NAEC-accredited comprehensive epilepsy centers:

Novant Health Forsyth Medical Center in Winston-Salem, a NAEC Level 3 epilepsy center for adults

Novant Health New Hanover Regional Medical Center in Wilmington, a NAEC Level 3 epilepsy center for adults and children.

Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center in Charlotte, a NAEC Level 4 epilepsy center that serves both adults and children at Novant Health Hemby Children's Hospital. The pediatric epilepsy center, directed by Dr. M. Ehsaan Shahnawaz (Waylon’s doctor), is one of only four NAEC Level 4 pediatric epilepsy centers in North Carolina.