There’s so much to say about nurse Debra Poteet that it’s hard to know where to start.

There’s the old-school white cap she still wears long after they went the way of the rotary dial phone. Then there’s her penchant for barking orders that runs contrary to contemporary work styles. Let’s not forget her patient-comes-first work ethic. Her late-career return to college – when others have an eye on retirement -- needs a prominent mention. So does her love and support for team members. And oh, she’s a master IV sticker who leaves colleagues in awe.

In short: “She’s a legend,” said her manager, Kim Vaziri. “She’s one of the hardest workers I know. She has a heart of gold, but she’s also been described as a drill sergeant. She loves getting work done and being efficient and being there for her patients.”

In honor of Women’s History Month, we share the story of Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center nurse Deb Poteet, whose journey captures the passion, resilience, dedication and commitment to service so many women have brought to health care.

A lifelong learner

Poteet graduated with an associate’s degree from Virginia Highlands Community College (its name today) in rural Abingdon, Virginia, in 1983. School was hard, with travel to clinical experience and education sometimes a two-hour drive. “You knew you had made it if you got your nursing cap and were pinned.”

She began her career in Virginia as a labor and delivery nurse in 1984. She moved to Charlotte in 1990 and has worked at Presbyterian Medical Center ever since.

A pesky regulation sent her back to school for her BSN (Bachelor of Science in Nursing) four years ago. “Deb does all the point-of-care stuff for the unit,” Vaziri said. “All of that is highly regulated. She's done all of this for years. But because she didn’t have her bachelor of science, she couldn’t sign off on the paperwork. So, here you have a nurse with like 35 years’ experience who needed someone to co-sign. She hated that. She decided to get her bachelor's so she could sign her own stuff and be treated equally.”

At age 60, she endured algebra and calculus to earn her BSN. On a roll, she soon started a master’s program. “That’s totally different from getting a BSN,” she said. “We had to turn in a paper every week.”

An instructor told her she needed help with writing: “You don’t even write in complete sentences.” Poteet countered: “Nurses don’t chart in complete sentences.” She had developed a writing style that was perfect for her profession but deemed lacking by the professor, who suggested she take a writing course.

Not one to back away from a challenge, Poteet enrolled in one at Central Piedmont Community College. But she soon learned a master’s degree wasn’t going to teach her more about patient care. And it was taking a lot of her time and energy. She decided it was best for her to train her energies on patients and teammates.

A day in the life

Stationed on the ambulatory care unit on the second floor of Presbyterian, she’s an air traffic controller of sorts on a floor where patients are being prepped for surgery. As team members wheel patients in and out of rooms, she commands her space with a no-nonsense demeanor that some might mistake as brusque. Or maybe it is brusque.

“What are you doing down there?” she calls to a certified nursing assistant entering vital signs into records.

Yvette Garcia, who was the subject of Poteet’s questioning, shrugs off Poteet’s style. “The way she talks,” Garcia said, “is not the way she is. She’s kind of like the only mom I have. We bump heads, but I love her.

“She’s tough but gets everything done,” she continued. “She runs a tight ship, but she has a heart of gold.” Years ago, when Garcia asked for a day off to raise money for her late sister’s headstone, Poteet came in the next day with $300.

That’s just what she does. “She'll give money on the side if she knows somebody’s struggling,” Vaziri said. “She doesn't want any credit. Ever.”

The vein-master

Nurses, techs and patients remark on how deft Poteet is at finding a vein in patients. “She’s the master of IV sticks,” said one, waving her arms in a mock bow of worship.

“She is the best IV stick ever,” Vaziri confirmed. “I'm telling you: I think we could blindfold her and put an IV in front of her and she could do it. Fastest thing I've ever seen. And patients love her for that. People will request her. They'll say, ‘I remember you from last time. I need you to start my IV.’ And when she has those requests, she goes in and starts the IV. I mean, like nothing.”

Poteet is quick to deflect the praise. “It’s just practice,” she said. “I’ve been doing this a long time.”

But there’s something else she credits for her true aim: her faith. “Sometimes you have to get on your knee before you go in a patient’s room,” she said. “I trust in the Lord. I couldn’t do this job if I didn’t. Sometimes patients want to know: ‘Do you go to church?’ I’ll talk to them about my church and my faith if they ask. I’ll pray with them.”

The changes she’s seen

A lot has changed in hospital care since Poteet earned her nursing cap and pin.

One wave of technology after another, for one thing. And “people go home sooner now,” she said. “And that’s a good thing. It costs them less, and there’s less risk of getting an infection.”

And then there are attitudes toward women. “In the 1980s, if a doctor walked in, the nurse had to stand up and give up her chair to him,” she said matter-of-factly. “That’s just how it was; it was a form of respect. Doctors didn’t know the names of nurses. They communicated and made rounds with the head nurse who would then relay to the other nurses whatever we needed to know.” Today’s approach is far more team-centered.

Is COVID-19 the scariest thing she’s seen in her long career?

“No,” she answered quickly. “That was the AIDS crisis. In the early days, we didn’t yet know what caused it. Some nurses were afraid to take care of AIDS patients – afraid they could contract it. There were some who refused. I saw it happening and thought: That’s not right.”

Of course, Poteet was unafraid to care for AIDS patients. This is her calling.

“We’re busier now because of COVID and taking more precautions,” she said. “There’s been a big learning curve. When you’re caring for a COVID patient, you have to project calm. And you have to do it with your eyes because the rest of you is covered up (in PPE). People are already scared to death. As a nurse, you can’t be scared when you walk in that room.”

‘The mystery behind her’

Not everyone can be gruff and lovable at the same time, but Poteet manages it with aplomb, Vaziri said. “She has a tough exterior … she’s been described as a drill sergeant. But on the inside, she is so tender and loving. I think that's the greatest thing about her and the mystery behind her.”

Poteet loves getting work done and being efficient and being there for her patients, Vaziri added.

“When Deb and I are together in a patient’s room, the patient will usually say to Deb, ‘You must be the boss,’” Vaziri said. “She'll be like: ‘Oh, no’ and point at me. And I say, ‘Oh, no, no, no. She’s the boss.' But she has never wanted this role. She just exudes that leadership quality.”

Poteet cares for her family as she does for patients. She grew up in southwestern Virginia with two brothers and two sisters. Her parents have passed away, but there are lots of nieces and nephews she’s close to. She tries to get to Virginia one weekend a month to visit her sister but may not make it that often in the winter. It might snow, and she doesn’t want to get stranded. “I don’t miss work,” she said.

Is there anything she’d change about nursing? “Not one thing,” she said. “I was chosen for this work. It’s what I was meant to do.”

As for that cap, it’s a message to patients she’s there for them. She stopped wearing it for a time, but she found patients couldn’t tell the difference between the techs and the nurses.

“I had a patient tell me one day she didn't know who her nurse was. And so, I said, OK. I started wearing my cap again,” Poteet said.

It’s also out of a sense of pride. “I’m so proud to wear my cap,” she said. “I had a lot of resistance when I put it (back) on because people said, ‘Why are you doing it?’ I want people to know I'm their nurse. If I'm coming into your room, I'm gonna take care of you.”

And she does.

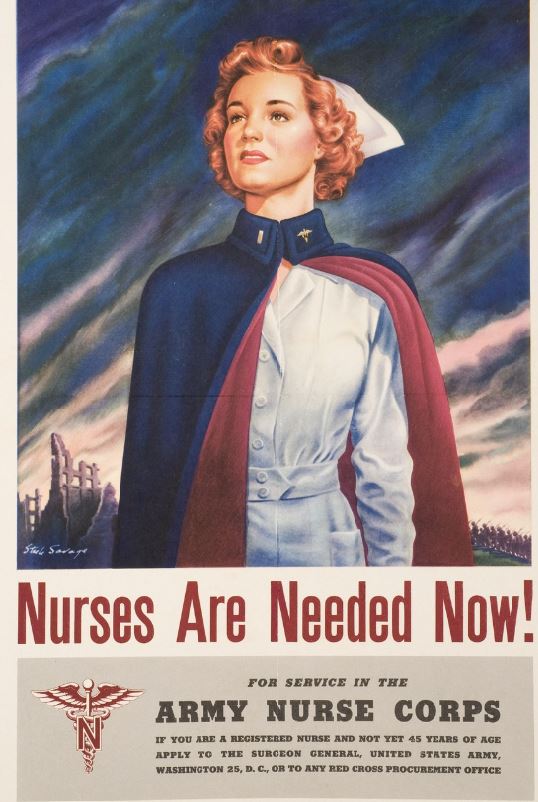

You will know her by her cap

The

nurse’s cap originated in the early Christian era when nuns, known as

“deaconesses,” wore white head coverings to indicate they cared for the sick.

Florence Nightingale (considered the founder of modern nursing) wore a nurse’s

cap in the 1800s.

Its

purpose through the ages was to signal to patients who the nurse – their

primary caregiver – was. That’s why Poteet still wears it. “People need

to know who’s taking care of them,” she said.

When

patients and new team members spy Poteet’s hat, they say things like, “You must

have been doing this a long time.” It’s become a conversation piece.

Nurses

get their caps at a capping-and-pinning ceremony, which is their initiation

into the sisterhood and brotherhood of nursing. The modern ceremony dates back

to 1855 when Nightingale was awarded the Royal Red Cross of St. George by Queen

Victoria.

Lapel

pins for nurses are still common, but the cap, not so much.