Her baby girl had stopped moving. And she was only 29 weeks pregnant.

So Courtney Melton, 35, went to the closest hospital (which happened not to be affiliated with Novant Health). When providers there told her she needed an emergency C-section but couldn’t adequately answer her questions, Courtney left and called the team she trusted: Providence OB/GYN, who met her at Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center.

There, maternal-fetal medicine doctor Dr. Elizabeth Ausbeck identified that her baby had fetal hydrops — life-threatening swelling and fluid buildup in her tissues and organs.

About half of all babies with this condition die before birth or soon after delivery. But Courtney’s baby wouldn’t be one of them.

Here’s how this baby got home.

The high-risk pregnancy care you and your baby deserve.

The statistics weren’t hopeful. But the parents-to-be were.

Sometimes, there’s an obvious cause for fetal hydrops — but this time, imaging and testing didn’t reveal one.

Undaunted, Ausbeck and maternal-fetal medicine colleagues Dr. John Allbert and Dr. Hytham Imseis proposed a plan: First, do an intrauterine fetal blood transfer since the baby was also anemic. Then, monitor Courtney and help the baby stay a few more weeks in the womb.

That’s because premature babies have a higher risk of disability and death, even before hydrops and underlying medical issues are added into the mix. Doctors couldn’t promise the extra time would save the baby, but it would give her more of a fighting chance.

The statistics weren’t hopeful. But Courtney and her husband, Luke Melton, 29, were.

The couple already had three children, and during Courtney’s last pregnancy, she’d been transferred to Presbyterian Hospital. She’d been so impressed with the care she received there from Providence OB/GYN that the couple had decided to use them again, even though it meant driving three hours round-trip from their home in Norwood, North Carolina, to each prenatal appointment in Charlotte.

They’d felt led to have this baby at Presbyterian, with this team. So they decided to trust.

‘Something was really wrong.’

The team’s goal was to get Courtney to 34 weeks of pregnancy, when the baby’s lungs would be almost fully developed — unless mother or baby became endangered sooner.

But at 32 weeks pregnant, Courtney developed preeclampsia overnight, then began rapidly taking on fluid in front of ob-gyn Dr. Kristi Balavage. The mother/daughter duo were experiencing a rare and dangerous condition called “mirror syndrome,” where Courtney’s body was “mirroring” the swelling of her baby’s.

The couple had been praying for difficult decisions to be made for them — and Balavage called this one: You need to have this baby now. Courtney felt peace wash over her, even as the operating room filled with activity.

“Going into a C-section, I wasn’t thinking, ‘She might not make it,’” Courtney said, although she secretly hoped all the worry was overblown. But when her baby came out, she looked visibly sick, had fluid on her head and stomach and was taken directly to the neonatal intensive care unit, or NICU, for stabilization. “It became a reality,” Courtney said. “That was very hard.”

How teamwork kept this little girl alive

But their baby girl stayed alive, thanks to the NICU team whose specialized and personalized care “blew us away,” Luke said. Although Courtney had given birth three times before, they’d never experienced the caregiver ratios of the NICU.

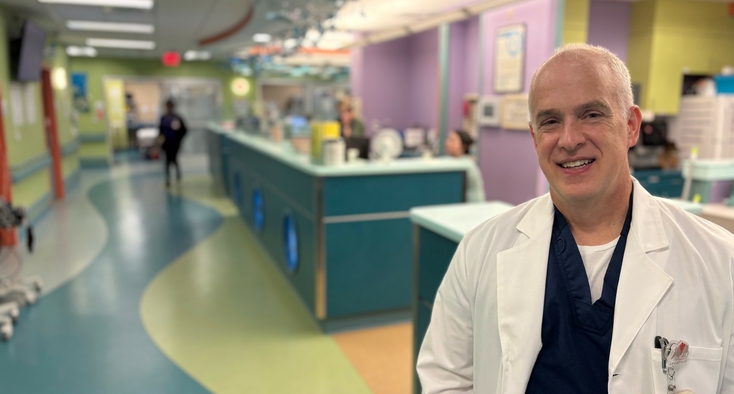

Pediatric surgeon Dr. Tuan Pham of Novant Health Pediatric Surgery - Elizabeth compares the NICU to a smoothly running airport, where hundreds of people behind the scenes help you get to your destination. The same is true in the NICU, where doctors, nurse practitioners, nurses, respiratory therapists, nutrition technicians, lactation consultants, medical geneticists, environmental services team members, case managers, surgeons, anesthesiologists and surgical technologists all work together to care for fragile babies.

On day three, Courtney got to hold her baby for the first time — and finally named her: Trinity Faith Melton. And on day four, Trinity had open abdominal surgery with Pham.

A mystery — solved

The cause of Trinity’s hydrops had been a mystery.

But Pham had a hypothesis, confirmed during the surgery: At some point in the pregnancy, a 2-inch segment of Trinity’s intestine had twisted and died, perforating her bowel and making a hole that allowed meconium (waste) to leave her intestine and enter her abdominal cavity.

To fight back, her body created a large pocket called a meconium cyst that surrounded the spilled meconium and sealed the contamination. Her body's response to the dead segment of intestine and the meconium contamination was whole-body swelling, or hydrops.

In short, even before she was born, this little girl was a fighter.

During surgery, Pham removed the damaged segment of Trinity’s intestine and placed a temporary ostomy (a new opening in the body to temporarily re-route waste into a pouch). The ostomy would allow time and opportunity for her bowel to heal, before another surgery to remove the ostomy and re-connect her intestines.

Doing complicated surgeries on the tiny body parts of premature babies can be challenging, especially in cases like these, since intestines that have been contaminated by meconium are prone to bleeding and breakdown.

But Pham — who works with children birth through age 18 — finds babies especially rewarding: “They heal so well,” Pham said. “They can be born with a defect, like an esophagus that didn’t fully develop or part of their intestines missing, but you do the right operation and they heal as if nothing has happened.”

And Trinity did. After eight weeks of post-surgical healing in the NICU, Pham performed Trinity’s second surgery, which went as planned. Once Trinity got the hang of eating and her newly re-linked digestive system was working, she left the NICU — just 10 weeks after being born early with a life-threatening condition.

‘We stuck in there together.’

There were challenges, but there were also blessings along the way. Courtney built relationships with other NICU moms, learning that “Somebody’s always got it worse than you — and in those low moments, we stuck in there together.”

She is grateful for every doctor and slew of other clinicians who cared for Trinity, especially the primary NICU nurses: “They’re what got us through.” But the care wasn’t just from medical staff.

“Everybody was great,” Courtney said. “The cleaning ladies helped. The cafeteria ladies would tell me, ‘I'm praying for your daughter,’ and they'd ask me about her. The ladies at the front desk cared. They always asked me, ‘How's Trinity doing?’ They knew her name.”

Luke is grateful for Pham, who performed the surgeries that fixed his baby’s digestive system and harbored a secret skill: When Trinity came back from surgery, one of her bandages had been shaped into a butterfly, much to everyone’s excitement.

A few days later, they found out Pham had been the artist. “He had taken the time to cut this little butterfly out of the bandage. He was super caring and just did that to make us smile,” Luke said.

Today, Trinity is home, getting the hang of eating, sleeping and being adored — sometimes too much — by three older siblings.

Pham expects her to have a normal childhood, without any developmental impacts from her surgeries.

Her parents call her a miracle: “Even when we didn't know what was going to happen and it seemed like the odds were stacked against us and stacked against her, that didn’t matter,” Luke said. “God was with us and handled everything perfectly.”