More than a century ago, as the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 gripped the globe, the biggest demand wasn’t for medicines, face masks or even new sanitation methods.

Communities wanted nurses, and there simply were not enough.

Overflowing field hospitals needed nurses to care for patients who had the worst cases of the killer respiratory disease. But a severe nursing shortage meant their requests often went unmet. As one pandemic-era telegram in response to a plea for nurses shows: “Can send all the Doctors you want but not one nurse.” In other words, none were available.

Emergency hospitals “sprung up in every major city – in school gyms, hotels, churches and other large gathering places,” said Phoebe Pollitt, a retired RN and associate professor of nursing at Appalachian State University in Boone. “Cities and counties begged for women to nurse the sick and care for those in emergency hospitals and in homes.”

Fast-forward to COVID-19 treatment today and the similarities are striking. Nurses — today women and men — are still the backbone of patient care. After a century of progress, ever more-sophisticated medical and nursing training and technological advances almost too huge to comprehend, one thing hasn’t changed: No one knows a patient like their nurse.

New, sanitary hospitals needed nurses

Pollitt, who studies the history of nursing in North Carolina, said professional nursing in N.C. got its start in the 1890s, following the Civil War. Training built on the traditional skills women learned from nursing family members and neighbors and serving as midwives. The war had proven the importance of cleanliness in the health care setting, and new civilian hospitals founded on the “germ theory” of disease needed nurses to staff them.

The nursing schools that opened at the turn of the century across the state taught women about nutrition, how to treat fevers and how to use new technologies such as thermometers, blood pressure cuffs and stethoscopes.

But the best treatments for the flu were rest, diet, hydration, cleanliness and isolation from others – care that nurses were trained to deliver. During the pandemic, nurses taught the Red Cross home nursing course, so non-nurses learned the basics of scientific care for the sick. One of N.C. nursing’s biggest projects was getting “sanitary privies” or outhouses for rural residents, where lax standards for personal refuse in fields led to hookworm and other disease.

Following the 1918-19 pandemic, “In the 1920s, the perceived and real need for nurses exploded in both hospitals and public health,” Pollitt said. Patients needed “light, heat, cleanliness, quiet … We’re still talking about those things. They haven’t changed much in the past 150, 200 years.”

Nurses at the bedside, in the boardroom

Today, it’s still unclear how the COVID-19 pandemic might change the nursing profession. But there is no question that nurses have been vital to providing care to patients, said Loraine Frank-Lightfoot, Novant Health vice president of nursing and chief nursing officer in the greater Winston-Salem market. An RN, she also holds a Doctor of Nursing Practice and a Master of Business Administration.

“There are some positives that come out of a stressful situation like this, where you have increased camaraderie, collaboration and recognition for the value of your colleagues,” she said. “The collaboration and respect between clinicians is stronger now than it was before.” A new generation of young nurses have witnessed scenarios that seasoned veterans never experienced in their entire careers.

She has concerns, too. She’s watched nurses leave the profession over health concerns and other issues with their families, and nurse managers are having to fill in the ranks with contract nurses who are highly qualified but don’t have the same commitment to the organization and the team.

One of Frank-Lightfoot’s nurses said the neighborhood kids won’t play with her children because of her role caring for COVID-positive patients.

Moments like that can create a whole other level of stress.

And then there’s the death they’ve seen over the past year. Nurses have long been a bridge between patients, their families and the health care system. Now, they’re the only ones holding a dying patient’s hand while the family watches via FaceTime and Zoom.

The medical journals are starting to report on increased anxiety and depression among health care workers because of such experiences.

“Those things make me concerned,” Frank-Lightfoot said. “I get a little choked up thinking about some of the stories they've told me, where they've seen a husband and wife and child all die from the same family.”

One of her hopes from the pandemic experiences is that there’s increased recognition of what registered nurses bring to the American health care system. In particular, she’d like to see nursing have a larger voice in decision-making – not only at the bedside, but also in the boardroom.

Nurses have a unique role in that they understand the science behind medical treatment and connect on a very personal level with patients and their families. That experience can make health care systems so much better, Frank-Lightfoot said.

The public, she said, doesn’t “understand the amount of education, experience, training, responsibility that nurses have. They spend their entire shift with patients, so they know those patients really well, and they navigate a lot of family dynamics and personal issues. There's a lot of complexities in nursing.

“They’re leaders. They're the soldier behind the scenes, making sure the care needed gets done.”

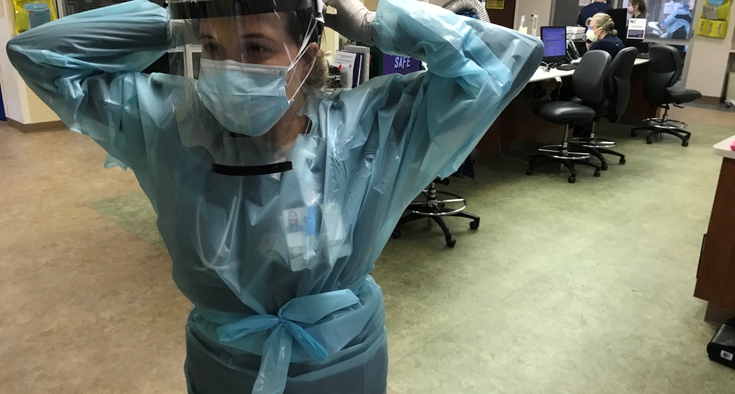

Caption top photo: Nurse Kathy Richardson at the COVID-19 ICU at Forsyth Regional Medical Center